Moveable stoppers

Early inspiration and exploration

I my early exploration into bar construction I saw posts from Mark Groshens on Power Kite Forum describing longthrow bar construction. The concept is to build a control system with lots of travel for the bar. This allows for a large and rapid depower. In some designs there is enough travel to reach zero bar pressure and the absolute maximum depower the kite can provide.

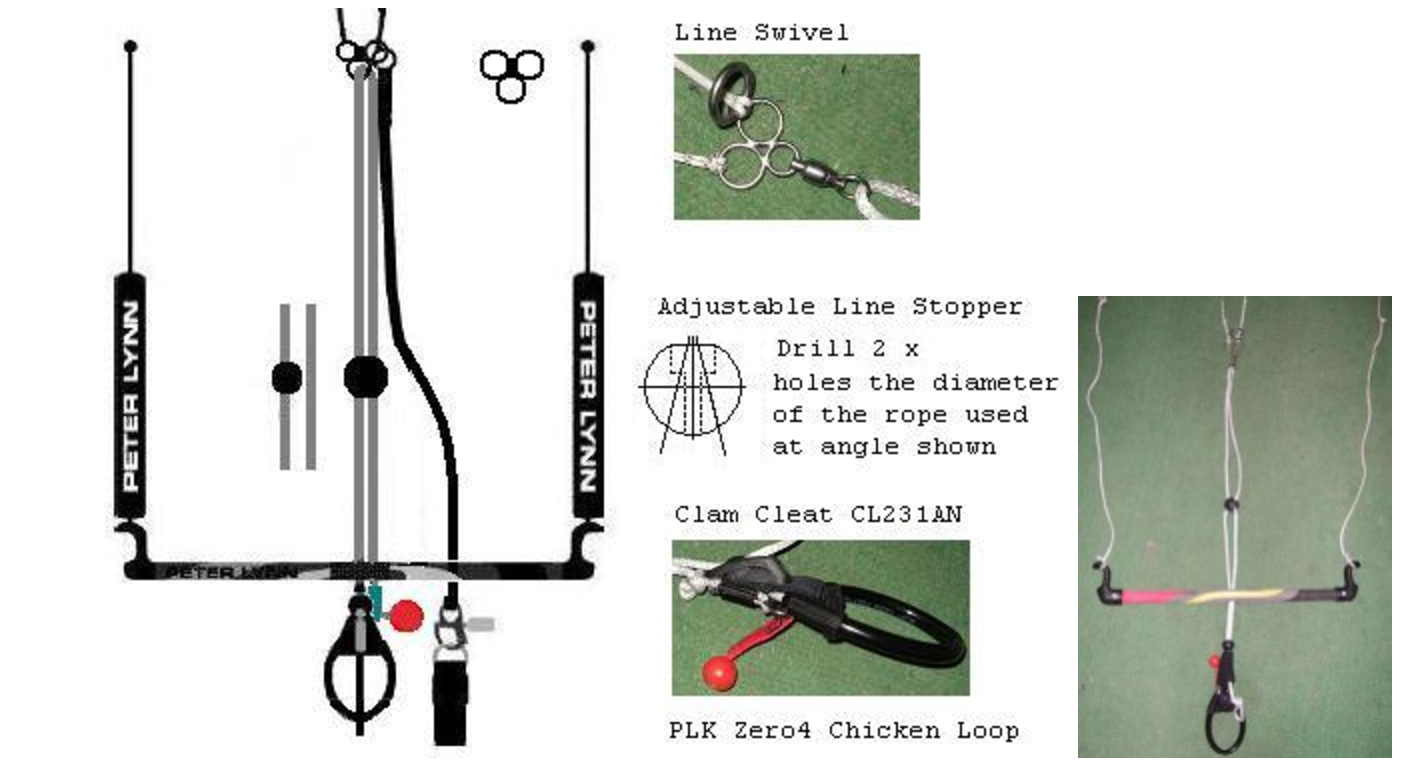

The work Mark described was with Arcs and is documented in the Arc Setup FAQ, specifically the section Control Bars - Custom Designs. The Arc Setup FAQ describes a long throw design with a doubled trim line, trim control below the bar, an adjustable line stopper that bends the paths of the pair of trim lines.

The stopper ball can be moved up and down the trim line while underway to limit the maximum excursion of the bar up the trim line. The bend in the trim line path allows the ball to hold its position with bar pressure against. At least that’s the idea. I never built a stopper exactly like the one shown here. I wasn’t sure the bars I was using would bend the line back and create the friction needed to keep the stopper in place. The bars shown in the design are, I believe, from Peter Lynn ‘04 or ‘07 control systems. These bars have a fairly narrow, perfectly round hole for the trim line. Such a passageway would force the trim lines together regardless of orientation. Some of the bars I was using had ovalized bores which I feared would catch on the spread trim lines coming out of the single-piece stopper. As such, I never made or tested this stopper. Having not tested it, I can only speculate how exactly the stopper would have behaved.

Two-piece stoppers

I elected to build my stoppers in two pieces: A block above to spread the trim lines on the pilot’s side with a ball below to bring them back together. The critical bend in the lines happens between the block and the ball. To make them function as a unit with single-handed control, they are joined with a segment of shock cord.

To move the two piece stopper you push the block toward the kite or pull the ball towards yourself. When the bar hits the ball, the ball will settle into the block, bend the trim line and not move further.

My first blocks were made of wood, but it proved problematic to manufacture. I quickly moved to Delrin acetal. Delrin is easy to work with wood-working tools, but lacks the complexities of wood grain. It’s stable in moisture and slippery against line, plastic, metal and wood.

The very first blocks had parallel pathways for the trim line. These stopped the bar just fine but the spread of the trim lines above the block was problematic. If you have a ring between the block and the cleat, gravity will send the ring down onto the spread trim line and cause the ring to stick. With the trim lines pressing against its inner diameter, the ring can’t spin freely when it needs to. The jammed ring can also impede the block’s motion up the trim line when the pilot pushes it. The ideal dimensions allow the ring to rest on top of the block without any pressure on the trim line.

Another more subtle issue is the minimum distance between the block and the cleat. As the trim lines enter the cleat, they can be adjacent to one another. If they are not adjacent to one another as they exit the block, they must take an angled path and the block cannot be pushed all the way to the cleat. It’s a small thing but for shorter pilots every millimeter between yourself and the cleat is a problem.

The Ball

The ball on the bottom of the stopper controls the interface of the stopper and the bar. Bringing the trim lines back together assures they can never press against the bore of the bar. The trim lines won’t impede travel or spin. Nor will they cause unnecessary abrasion of the bar’s bore.

Using a sphere and a round rim on the kite-side of the bar’s bore assures the bar can self-center on the trim line and spin freely. The low friction of the Delrin further reduces impediments to a free spinning bar. These features allow the bar to spin freely even under high load if that is desired.

Yes, but how does it fly?

The result of this work is a stopper that stays where you leave it. Repeated slams of the bar against the stopper do not move it. In steady winds and long runs you can set it where you want it and fly the kite with two fingers on the tip of the bar. If you are on a 20 minute tack this can be quite a relief.

If you are flying at full speed you can set it just shy of where you would start sliding and fine tune the position with your hand pulling the bar just millimeters off the stopper. Should you loose your grip or have to let go for a moment the bar will rest on the stopper at near full load while you readjust.

If I’m jibing a lot I’ll often set the stopper out a bit so that I have a moderate amount of load even when I let go of the bar. I’ll let go of the bar briefly during the jibe as the kite is passing through the power zone. At the same time I kick the bar to untwist the lines. Moments later the twists are out of the line and the kite has passed through the power zone. Before the kite reaches the edge of the wind window and I grab the bar and trim the kite for cruising again.

If conditions are gusty push the stopper all the way to the cleat. This gives you access to the full range of depower when you let go of the bar.

If you hand your kite to a shorter flying who lacks your wing span, the stopper is quick hack to make the adjustments they need. Just pull the stopper in a little, trim the kite in to match via the cleat and give the kite to the other pilot. They might not be able to reach the cleat, but the bar and stopper will never be too far away. The stopper is never any further away than you can push it.

Where do we go from here?

This the early design of the stopper created before I made accommodations for a flag line. That’s an article for another day, but everything here still applies when solving that problem.